“Since the beginning, a century ago, the United Fruit Company developed wilderness areas where bananas would commercially grow. They always seemed to be at the end of the world…”

Clyde Stephens, a world renowned banana expert, historian, author, scientist, and gregarious frontier man, has spent decades in sweltering plantation backwaters; ‘nowhere places’ where the tropical jungle wrestled against the tenuous ‘civilization’ of United Fruit townships, and won. He looks exactly how you’d expect: undaunted by much, and seasoned.

“I was first assigned in 1959,” he says, recalling a thirty-two year career in the company’s research department. “I was fresh out of the University of Florida and it was my first job and I had a bachelor’s degree in entomology.”

Clyde was posted to Bocas del Toro province in Panama, a stretch of luxuriant Caribbean coastline near the Costa Rican border, a land disconnected from the outside world (until road connections came in the 1980s). He became fascinated by the region’s dazzling ethnic and ecological enclaves, its indigenous and African-descent peoples, its teeming rainforests and mangroves, and its scintillating off-shore archipelago, dubbed “the Galapagos of Panama” for its scores of biologically unique islands and islets. Between working for the UFC and raising a family with his wife, Phyllis, Clyde penned four books on the history of the region.

Clyde was posted to Bocas del Toro province in Panama, a stretch of luxuriant Caribbean coastline near the Costa Rican border, a land disconnected from the outside world (until road connections came in the 1980s). He became fascinated by the region’s dazzling ethnic and ecological enclaves, its indigenous and African-descent peoples, its teeming rainforests and mangroves, and its scintillating off-shore archipelago, dubbed “the Galapagos of Panama” for its scores of biologically unique islands and islets. Between working for the UFC and raising a family with his wife, Phyllis, Clyde penned four books on the history of the region.

Today, his wood-built home occupies the western tip of Solarte Island, a place known as Hospital Point after the pioneering United Fruit medical center which operated there in the early 20th century; remnants of its stone foundations can be discerned in the grounds. The garden is immaculately groomed and filled with botanical specimens from around the world: vivid flowers, fruit trees, and one gigantic talipot palm, Corypha umbraculifera, a species which reaches heights of 25m and takes up to 80 years to bloom.

The March of the Banana Republics

As we drink coffee in the shade of the trees, surrounded by the chatter of wild parakeets, Clyde describes the history of banana production in Bocas. The United Fruit Company formed in 1899, he explains, when Minor Keith’s Central America-based Tropical Trading and Transport Company merged with its main rival, Lorenzo Baker’s Caribbean-based Boston Fruit Company. Keith, an ambitious young American railroad tycoon, had laid down pioneering train lines in Costa Rica and raised a modest banana empire “along the tracks.” But he soon ran into financial trouble and was forced to humble himself before his nemesis. The merger of their two companies would prove lucrative beyond all expectation. Based in Bocas del Toro, the UFC rapidly expanded through Central and South America, consuming territories and competitors on both Pacific and Caribbean shores, evolving into a behemoth empire that boasted its own railroads, steam ships, townships, and ports.

Today, United Fruit is no more; its operations have been scaled back and its holdings fragmented into a plethora of subsidiaries. Its direct successor is Cincinnati-based Chiquita brands (look for the blue stamp and the “Miss Chiquita” logo, modeled on Brazilian samba singer Carmen Miranda).

In Bocas del Toro, Chiquita’s only surviving division is based in the capital of the province, Changuinola City. It is a hot, grungy, terminally shambolic town perched on the mainland between languid swamps and a cloak of dense plantations. Daily life for its 30,000 inhabitants is timed by the buzz of yellow crop dusters soaring back and forth. An island of order in a sea of dilapidation, the tranquil neighborhood of Finca 8 is the setting for Chiquita’s headquarters, along with the largest and most prestigious houses in town, the sole preserve of company executives. Nearby, the leafy Changuinola Golf Club boasts a swimming pool and a nine-hole course.

“Banana divisions were always built in an orderly fashion,” explains Clyde. “Well laid out, very formally, straight from the drawing board. These were attractive Company towns and designed to hold and keep professional employees and families, especially the foreigners — mostly American skilled employees. These were very isolated areas and all the amenities had to be provided to keep employees for the long term, not just a year or so.

“This means good housing, schools, hospitals, medical clinics, recreation like golf courses, country club, tennis, pool, parties, club activities to bond people. We were a special pampered breed and people like us never changed employers and retired after 40 years.

“Not only foreigners, but lower monthlies and labor classes also got good treatment for the same reasons: orderly labor camps, electricity and good water for the first time in their lives, company built and run schools, a steady job with benefits, medical care in the company hospitals and clinics, the eternal soccer field in the middle of the labor zone, a store for provisions in every camp…”

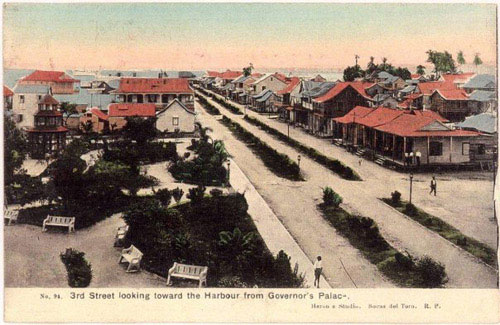

At its heyday in the early 20th century, the UFC managed its affairs from Bocas Town, a wood-built port perched on the tip of Columbus Island (today known by its Spanish name, Isla Colón). It was the epicenter of a thriving multi-cultural milieu. English and French-speaking labourers were shipped en-masse to the steamy Bocatorean shores from Caribbean colonies like Barbados, Jamaica, Haiti, and French Guadalupe. In total, more than 50 nationalities were represented. It was a swinging time, when modernity burst onto the scene with staggering new advances in technology. The company established the Tropical Radio Telegraph Company, signaling a bold new age of mass communication in Central America. Three newspapers were distributed around town, keeping the population abreast of news and social functions. There were movie theatres, horse-races, cricket, baseball, and polo matches.

Off-shore, the company’s “Great White Fleet” plied the oceans with their bounty, delivering cheap, sweet bananas to a mass market for the first time in history. On the mainland, new infrastructure was erected: railroads, bridges, and the impeccably attired port of Almirante. There was the sense that man’s ingenuity and spirit of enterprise could overcome any obstacle.

A Human Struggle in the Tropics

But behind the crisp white façade of every immaculately ordered UFC township was a much darker tale of human struggle. Blazing sun, torrential rain, floods, bugs, landslides, and a profusion of feverish diseases were the reality for those workers charged with forging settlements from the wilderness.

Historically, Bocas del Toro had been so overgrown and inhospitable, so voracious and all-consuming, that even the conquistadors, with their insatiable lust for gold and power, had never managed to tame it. From the 16th century to the mid-1800s, Bocas was little more than an uncharted frontier.

“It was a kind of a refuge for sea-faring peoples,” Clyde describes Bocas del Toro. “Turtlers, fishing people, adventurers. They’d get off the wild rough sea out there in the Caribbean and squirrel into here, at Old Bank, Bastimentos island. And later on, where Bocas Town is today, that developed into a little fishing village and a little population settled there, but that was the only settlement around here, so to speak.”

The cornerstones of “civilization” were laid in the 1880s, when the German Empire began to reach the most far-flung places on the planet. An early fruit pioneer, Jochen Ludwig Heinrich Hein, acquired lands on the Bocas mainland, planted bananas, and struck green gold. Among his extensive properties were swathes of highly desirable but entirely inaccessible flood plain on the Changuinola river, where the rich silt loam was ideal for large-scale commercial plantations.

The only way into the area, explains Clyde, was via the mouth of the river, but impossible to pass due to its violent currents and shifting sand bars. Hein died a rich man, but without ever exploiting those lands. Thus the task of broaching the Changuinola flood plain fell to three Americans, the Snyder brothers, who procured his estate in 1896. In the true spirit of the age, they revolutionized banana production, hauling fruit on narrow gauge tram roads with flat-bed locomotives. They were the big family in bananas in the 1890s. At the turn of the century, they sold out their holdings to the burgeoning new United Fruit Company. But Michael Snyder made one final, vital contribution to the industry: he carved a canal between the Changuinola river and an ocean channel just off the northwest tip of Columbus island, Boca del Drago. Thus began a vast, lucrative new chapter in the history of the banana business.

Boom, Bust, Repeat

For years thereafter, the Snyder canal served as the main artery for the transportation of materials, laborers, and fruit. Thousands of bunches were loaded onto barges daily for shipping out of Columbus Island. The United Fruit Company, it seemed, had brought the willful chaos of the tropics under control.

But no sooner had the champagne corks popped, that nature hit back. One by one, plantations began to fall to a mysterious and deadly infection. Plants withered, their umbrella-like leaves yellowing and folding dead from dehydration. ‘Panama disease’ was a kind of fungus disease incubated in the soils, spread by floodwaters, carried by man in the rhizomes (bulbs for growing new plantations).

“They just hauled this horrible disease everywhere they went,” says Clyde. “By the 1920s, all of Changuinola was out of bananas. The banana plantations had died out.”

Thus the UFC was forced to keep moving north, opening up remote lands in the Talamanca valley on the Costa Rican border. Within a decade, those plantations were dead too, or had suffered massive flood damage from the powerful rivers emerging from the continental divide. Bridges, railroads, and housing were washed out. Defeated, the UFC relocated its entire division to the Pacific coast. In Bocas, cacao was planted in place of bananas, but as a less labour intensive crop, thousands of workers were left unemployed. Many departed for the Panama Canal Zone, the thriving commercial ports of Colón or Panama City. Others became subsistence farmers dwelling on the fringes of the forest. In a region destined to weather boom-and-bust cycles like a stubborn old sailor, images of decay became commonplace; the jungle reclaimed its own.

In the 1940s, the second world war brought a surprise change of fortunes when the Japanese cut off the world’s supply of abaca, from which Manila hemp, the raw fiber in rope manufacture, is derived. Unable to tie their warships, the US government enlisted the UFC to grow abaca on an industrial scale. Bocas was suddenly booming again. Some 3000 Latino laborers were flown in from neighboring Central American countries, and for the first time in its history, the province became predominantly Spanish speaking.

In the 1940s, the second world war brought a surprise change of fortunes when the Japanese cut off the world’s supply of abaca, from which Manila hemp, the raw fiber in rope manufacture, is derived. Unable to tie their warships, the US government enlisted the UFC to grow abaca on an industrial scale. Bocas was suddenly booming again. Some 3000 Latino laborers were flown in from neighboring Central American countries, and for the first time in its history, the province became predominantly Spanish speaking.

After the war, the Philippines resumed its role as the world’s supplier of abaca and Bocas fell into decline, but not for long. In the 1950s, the UFC made a historic decision to plant new disease resistant varieties of bananas. The venture was a high success and Changuinola was soon on its feet, producing fruit for the world. Soon waves of indigenous Ngabe migrants arrived, adding a new cultural dimension to the town.

The mood was buoyant, but no empire lasts forever. Against a backdrop of waning U.S. influence, the United Fruit Company, “Mama Yunai” to its workers, “el pulpo” (the octopus) to its critics, was soon the object of an anti-trust action under the Eisenhower administration, and forced to release its monopolistic grip on the industry.

Combining ruthless efficiency with a rapacious determination to dominate, in so many ways, the company had been a prototype for today’s multinational corporations. By the time of its close, political lobbying and outright bribery were par for the course; the term “Banana Republic” had entered the public domain and the company’s reputation was forever tarnished by a series notorious episodes in Guatemala and Colombia. In the end, politics, the tool that had helped sustain the company through the glory years, was to be its downfall. Slowly, inexorably, the United Fruit Company broke apart.

Decomposing Like a Banana Peel

“It all began to fall apart when overnight organized squatters supporting the Noriega government occupied both sides of the railroad. This was organized and tolerated by the military government to get support, and the company was helpless to remove hundreds of invaders along the tracks.

“The results are seen today just after you cross the bridge over the Rio Changuinola all the way past the airport. It is pure disorganized chaos in buildings, shacks, hovels, horrible sanitation and disorder in housing and business. No intentions or fault of the Company. Past history now, but most people have no idea why that horrible mass called Changuinola City got that way…”

Today, up and down the coast of Bocas del Toro, the last vestiges of the UFC are in a state of vivid decomposition. The once handsome garden city of Almirante continues to serve as a banana shipment point, but has long since fallen into ruin, its population housed by disheveled shanties that clamber precarious over the black water swamps. Likewise, Sixaola is a dismal border town, slowly sinking into a torpid mire.

Today, up and down the coast of Bocas del Toro, the last vestiges of the UFC are in a state of vivid decomposition. The once handsome garden city of Almirante continues to serve as a banana shipment point, but has long since fallen into ruin, its population housed by disheveled shanties that clamber precarious over the black water swamps. Likewise, Sixaola is a dismal border town, slowly sinking into a torpid mire.

In Changuinola, decaying infrastructure lies scattered throughout town, a catalogue of enormous antique machines, old towers and industrial rigs, clapped out diggers, drills and cranes, now collapsed on their sides. They are flushed green under a swell of foliage, and through the alchemy of nature, transformed into vast ferric mounds of earth and wild flowers. Along the abandoned warehouses, great chimneys rise like the crooked horns of some weary colossus, who having accepted his destiny, whose furnaces are now starved and cold, has sunk to his belly to die.

To be fair, there are also tentative signs of regeneration: a newly expanded highway, a modern supermarket, and the most banal of all imperial multi-national outposts, a branch of McDonalds. The days of frontier bravado may be long gone, but thanks to Clyde Stephens, his work and his books, a valuable inside perspective on Bocas has been documented for future generations.

Source: Perceptive Travel